Accumulator 101

- Blog >

- Accumulator 101

Originally featured on DZone

Motivation

GSQL is a Turing complete Graph Database query language. Compared to other graph query languages, the biggest advantage is its support of Accumulators — global or attachable to each vertex.

In addition to providing the classic pattern match syntax, which is easy to master, GSQL supports powerful run-time vertex attributes (a.k.a local accumulators) and global state variables (a.k.a global accumulators). I have seen users learning and adopting pattern match syntax within ten minutes. However, I also witnessed the uneasiness of learning and adopting accumulators for beginners.

This short tutorial aims to shorten the learning curve of accumulator. Supposedly, after reading this article, everyone can master the essence of accumulator by heart, and start solving real-life graph problems with this handy language feature.

What Is Accumulator?

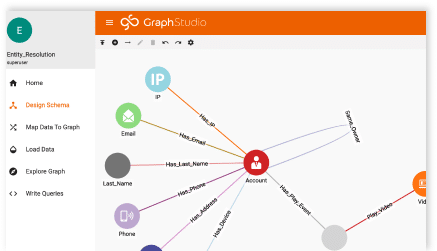

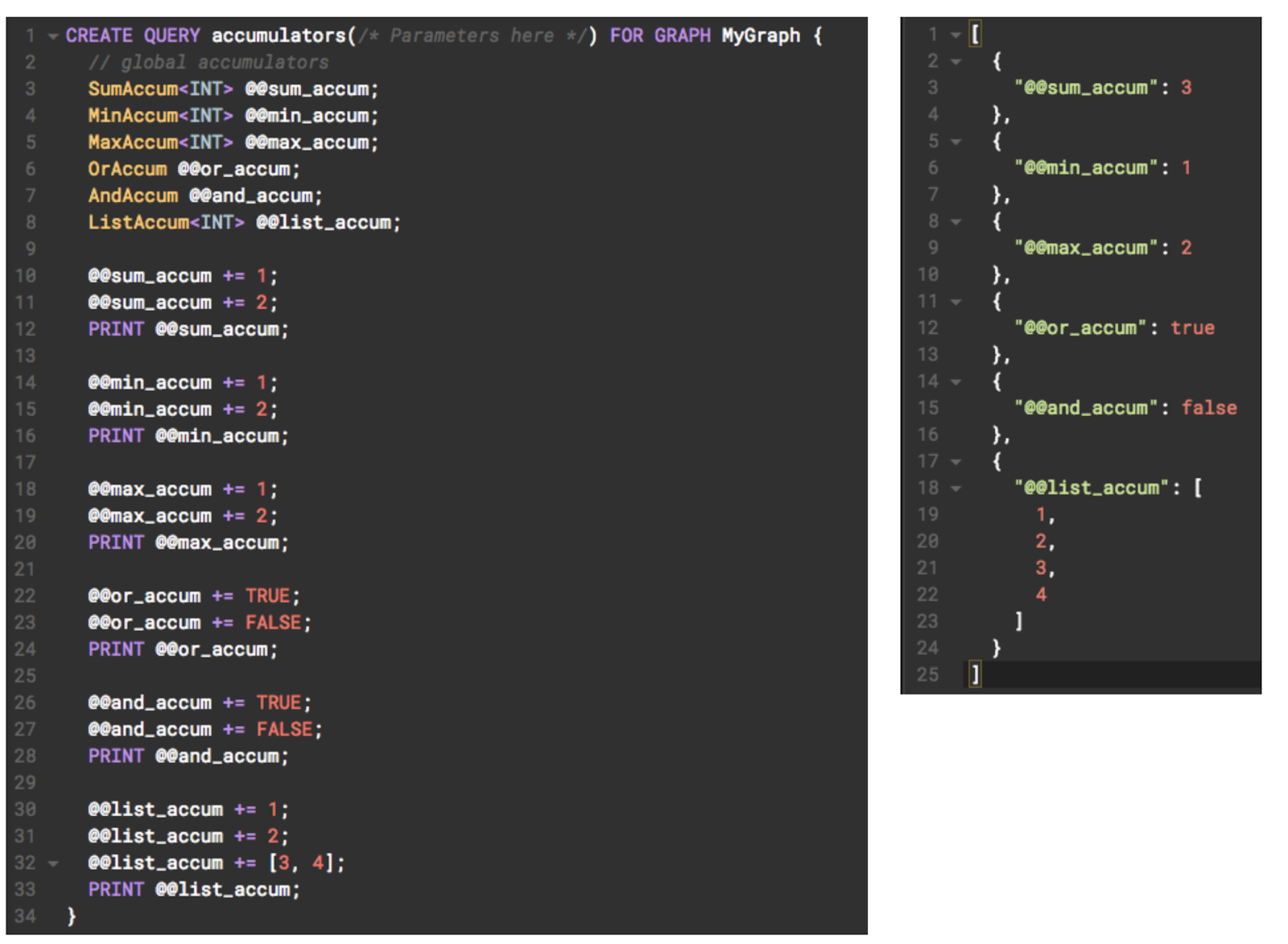

Figure 1. The left box is a GSQL query with different accumulators being accumulated. The right box shows the accumulator variables’ final results.

Accumulator is a state variable in GSQL. Its state is mutable throughout the lifecycle of a query. It has an initial value, and the user can keep accumulating (using its “+=” built-in operator) new values into it. Each accumulator variable has a type. The type decides what semantics the declared accumulator will use to interpret the “+=” operation.

In Figure 1’s left box, from lines 3 to line 8, six different accumulator variables (those with prefix @@) are declared, each with a unique type. Below, we explain the semantics and usage of them.

SumAccum<INT> allows the user to keep adding INT values into its internal state variable. As the lines 10 and 11 have shown, we added 1 and 2 to the accumulator, and ended up with the value 3 (shown in line 3 on the right box).

MinAccum<INT> keeps the smallest INT number it has seen. As the lines 14 and 15 have shown, we accumulated 1 and 2 to the MinAccum accumulator and ended up with the value 1 (shown in line 6 on the right box).

MaxAccum<INT> is symmetric to MinAccum. It returns the MAX INT value it has seen. Lines 18 and 19 show that we send 1 and 2 into it, and end up with the value 2 (shown in line 9 on the right box).

OrAccum keeps ORing the internal boolean state variable with new boolean variables that accumulate to it. The initial default value is FALSE. Lines 22 and 23 show that we send TRUE and FALSE into it and end up with the TRUE value (shown in line 12 on the right box).

AndAccum is symmetric to OrAccum. Instead of using OR, it uses the AND accumulation semantics. Lines 26 and 27 show that we accumulate TRUE and FALSE into it and end up with the FALSE value (shown in line 15 on the right box).

ListAccum<INT> keeps appending new integer(s) into its internal list variable. Lines 30 – 32 show that we append 1, 2, and [3,4] to the accumulator and end up with [1,2,3,4] (shown in lines 19-22 on the right box).

Global vs. Vertex-attached Accumulator

At this point, we have seen that accumulators are special typed variable in GSQL language. We are ready to explain the global and local scope of them.

Global accumulator belongs to the entire query. Anywhere in a query, a statement can update its value. Local accumulator belongs to each vertex. It can only be updated when its owning vertex is accessible. To differentiate them, we use special prefixes in its identifier when we declare them.

@@ prefix is used for declaring global accumulator variable. It is always used stand alone. E.g @@cnt +=1.

@ prefix is used for declaring local accumulator variable. It must be used with a vertex alias in a query block. E.g. v.@cnt +=1, where v is a vertex alias specified in a FROM clause of a SELECT-FROM-WHERE query block.

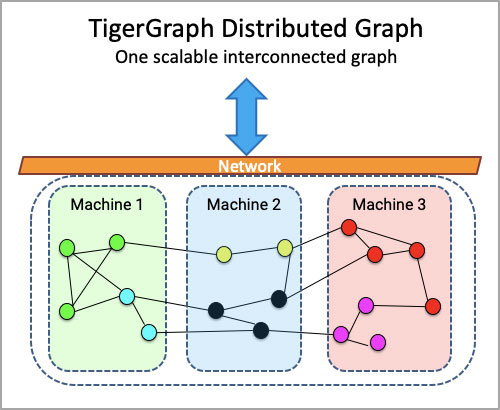

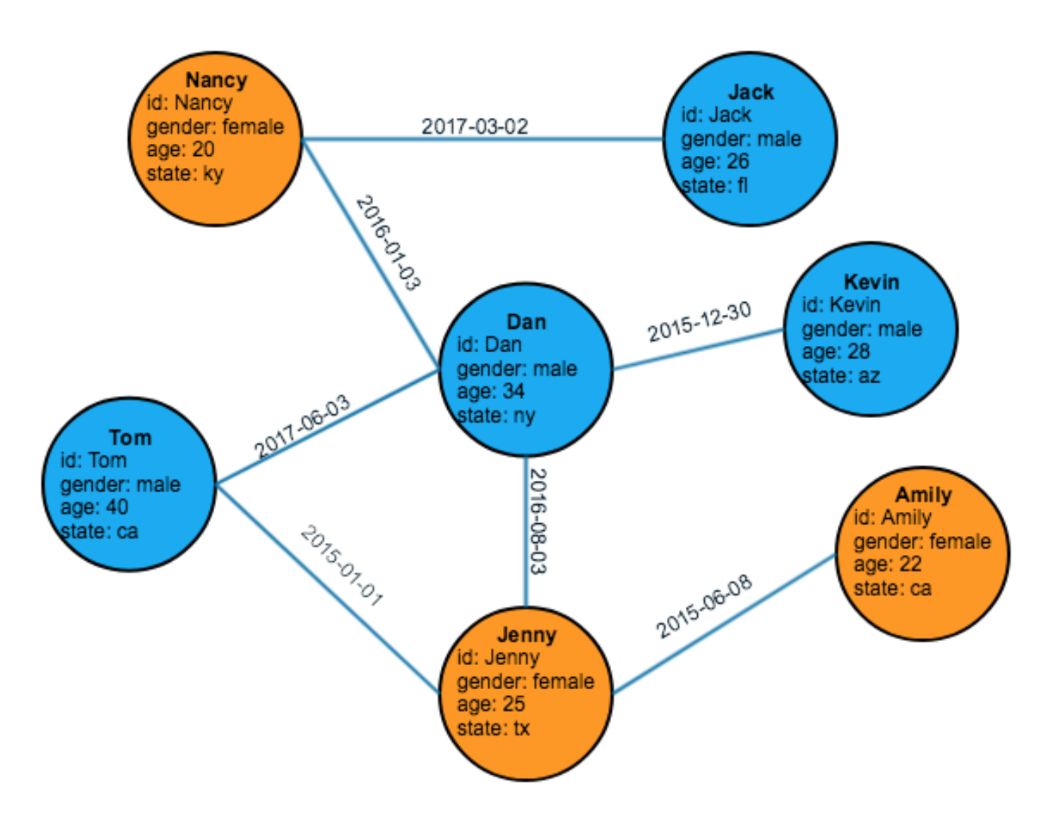

Figure 2. A social graph with 7 person vertices and 7 friendship edges connecting them.

Consider a toy social graph modeled by a person vertex type and a person-person friendship edge type shown in Figure 2. Below we write a query, which accepts a person, and does 1-hop traversal from the input person to its neighbors. We use @@global_edge_cnt accumulator to accumulate the total edges we traverse. And we use @vertex_cnt to write to the input person’s each friend vertex an integer 1.

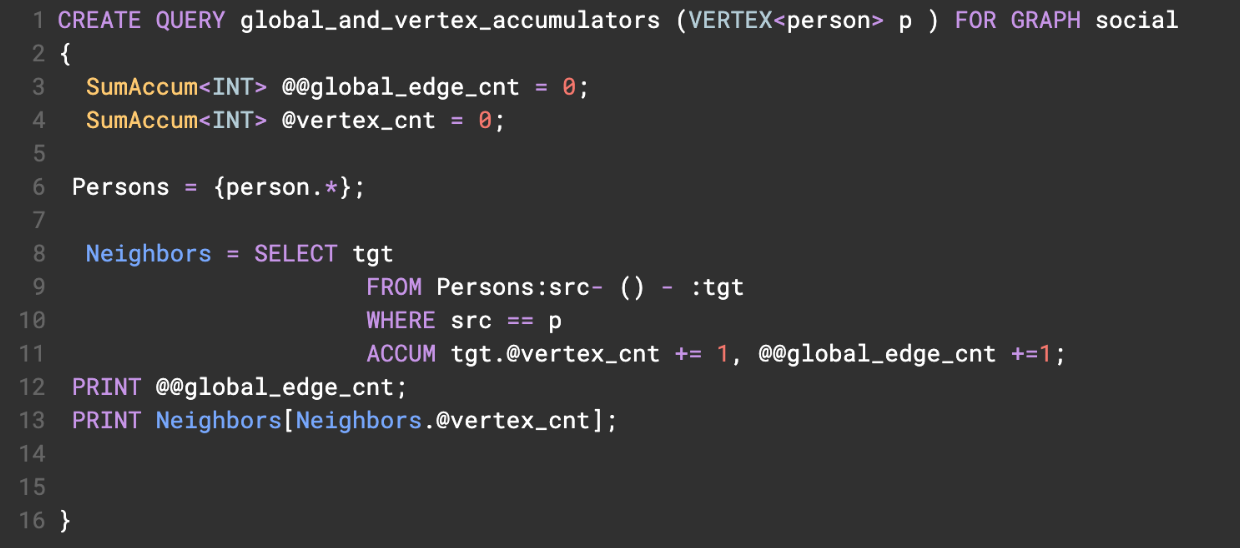

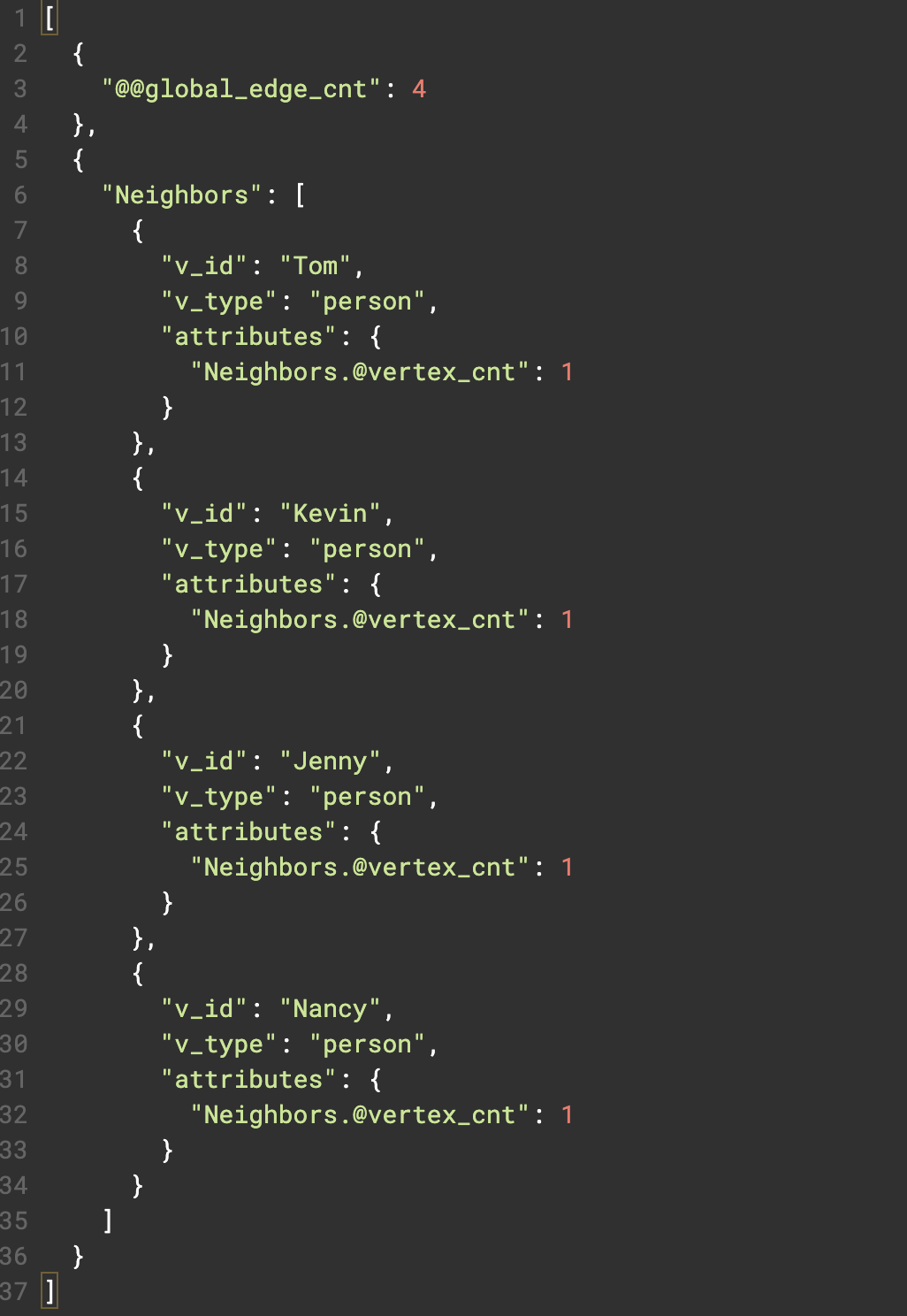

Figure 3. The top box shows a query that given a person, accumulate the edge count into @@global_edge_cnt. The bottom box shows that for each friend of the input person, we accumulate 1 into its @vertex_cnt.

As Figure 2 shows, Dan has 4 direct friends — Tom, Kevin, Jenny, and Nancy, each of which holds a local accumulator @vertex_cnt. And the @@global_edge_cnt has value 4, reflecting the fact that for each edge, we have accumulated 1 into it.

ACCUM vs. POST-ACCUM

ACCUM and POST-ACCUM clauses are computed in stages, where in a SELECT-FROM-WHERE query block, ACCUM is executed first, followed by the POST-ACCUM clause.

ACCUM executes its statement(s) once for each matched edge (or path) of the FROM clause pattern. Further, ACCUM parallely executes its statements for all the matches.

POST-ACCUM executes its statement(s) once for each involved vertex. Note that each statement within the POST-ACCUM clause can refer to either source vertices or target vertices but not both.

Conclusion

We have explained the mechanism of accumulator, their types, and the two different scopes–global and local. We also elaborate the ACCUM and POST-ACCUM clause semantics. Once you master the basics, the rest is to practice more. We have made available 46 queries based on the LDBC schema. These 46 queries are divided into three groups.

You can follow GSQL 102 to setup the environment. You can also post your feedback and questions on the GSQL community forum. Our community members and developers love to hear any feedback from your graph journey of using GSQL and are ready to help clarifying any doubts.